Andrew Chen is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz. Previously, he led the Rider Growth teams at Uber. He holds a B.S. in Applied Mathematics from the University of Washington. He is a prolific writer and insightful Twitter participant. Speaking of Twitter, some of the quotations below are compiled from tweetstorms and are marked with an asterisk.

- “Without growth, you have nothing, and the status quo is death.” “Scaling growth is hard.”

In one of his many blog posts, Chen points readers to a quote by the co-founder of Y Combinator (Paul Graham), who frames the challenge well:

“A startup is a company designed to grow fast. Being newly founded does not in itself make a company a startup. Nor is it necessary for a startup to work on technology, or take venture funding, or have some sort of ‘exit’ The only essential thing is growth. Everything else we associate with startups follows from growth.”

Generating greater growth is such a big challenge that many businesses today have created dedicated “growth teams.” A growth team’s mission is to understand, measure and improve the flow of users into and out of the products offered by a business. Every aspect of a product has the potential to help make the business grow. Or not. The opportunities for a growth team to create growth by making wise product choices are nearly endless since it is simply not possible for a product to be technically neutral. For example, there are many ways to reduce friction, expose new value and facilitate sharing to create new value for a business.

The success of a growth team is measured by metrics which can ladder up or down depending on the starting point (top down or bottoms up). On a top down basis you can see from a macro point of view how the business is performing in trying to grow the net present value of future cash flows. One a bottoms up basis you can see on a micro basis how the business is performing in growing the net present value of the cash flows of each customer. Accounting rules and regulations require that business a top down assessment of the business but too many firms do not do the bottoms up analysis. What is lost by only looking top down is the opportunity to capitalize on the fact that customers are heterogeneous rather than homogeneous. Some customers are much more profitable than others. Modern data science tools and systems allow the business to closely track this heterogeneity. Optimizing business processes for an average customer is often highly significantly sub-optimal because of the high variability of customers. Without a the benefit of a process of that looks at the business on the basis of customer by customer data, a major opportunity for the business can be lost.

Growth teams track and measure customer journey in terms of a customer acquisition funnel. The term funnel is a metaphor for a process which tracks and measures how effectively a business is attracting, engaging, converting, and retaining its customers. Chen’s recent tweetstorm’s about topics like funnels will resonate with anyone who is or has worked with a growth team. While the results of the work of a growth team can be tracked an measured quantitatively often what produces the results is qualitative since a business is not a machine but rather the outputs of a nest of complex adaptive systems. The reality is that not everything that matters can be counted and not everything that can be counted, matters. What this means is that a modern growth team does as its work is both an art and a science. Reconciling both top down and bottoms up models is required.

- “Growth is an after effect of strong product/market fit and great distribution.”

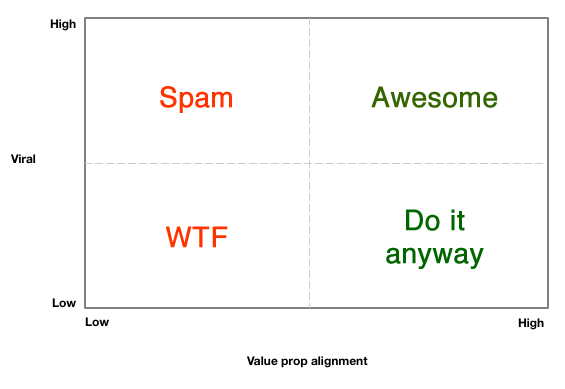

If the product isn’t something that people want to pay money for no amount of effort by a growth team will achieve the objective. Y Combinator’s Jessica Livingston puts it this way: “Our motto is to make something that people want. If you create something and no one uses it, you’re dead. Nothing else you do is going to matter if people don’t like your product.” Great growth teams magnify what consumers love about a product and how they spread that love. Too many businesses charge off trying to grow before they have product/market fit and die. The pressure to grow a business can be enormous, but if the product/market fit does not exist the message being sent is negative (i.e., it is spam).

- “Addiction to paid ads is bad.”

After some low hanging fruit is harvested (i.e., after some friends and family buy the product), acquiring customers will always cost real money. This is an unavoidable truth. A business can acquire customers with paid marketing (inorganic) or acquire them by using the product itself or aspects of the product as the means or acquisition (organic). Some customer acquisition cost very little and some costs an enormous amount. Whether that sales load can create net present value (NPV) depends on the totality of the unit economics of the business. Life is better if your CAC is not too high. What is too high? It depends. But as in the story Goldilocks and the Three Bears and with product/market fit you will know I when you feel/see it because it will be “just right.”

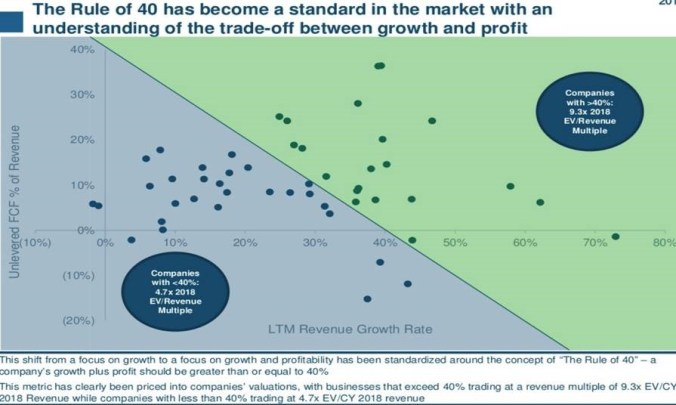

Inorganic customer acquisition via paid marketing is one of the fastest methods ever invented for a business to consume cash. It is also one of the easiest ways to “strand” capital since customers can leave before the business recovers that cost of customer acquisition. Some businesses today spend huge amounts of money to acquire customers. Rules of thumb like the “Rule of 40” have been developed to give business some guidance. Fred Wilson describes the rule with some examples:

“If you are growing 100% year over year, you can lose money at a rate of 60% of your revenues

If you are growing 40% year over year, you should be breaking even

If you are growing 20% year over year, you should have 20% operating margins

If you are not growing, you should have 40% operating margins

If your business is declining 10% year over year, you should have 50% operating margins”

This chart below illustrates how no two companies are quite the same as measured by the rule and that there is significant variability.

The Rule of 40 is not the only factors to be considered since you must also consider free cash flow, whether the business is generating network effects and the ability of a business to raise funds at an attractive rate and other factors I have written about on this blog. Kristina Shen of Bessemer Venture Partners believes:

“…Growth will always be the most important metric in terms of numbers that help indicate your valuation. We believe that looking at an Annual Recurring Revenue to Growth (ARRG) multiple will be one of the great valuation frameworks that you can leverage as you go forward. What are some of the other valuation frameworks we can look at? Growth is always going to be the one we look at the most, but some of the others we look at, as well, your cap payback and your sales efficiency. Your churn, looking at what percentage of your customers are retaining on an annual basis. Your cash flow efficiency, which we define as your net new ARR divided by your net churn.”

To calculate the ARRG multiple, divide the ARR multiple by year-over-year growth.

This dynamic complexity and the inability of a “capital allocator” to reduce the determination to a formula is part of what makes business and investing so much fun. All models are wrong, but some are useful. Sorting all this out in the best possible way is what makes a world class CFO so valuable. The CFO must take many factors into account including the current and likely future states of the capital markets. Looking at this set of issues in mid 2018, it may seem to some people that cash will never again be scarce, but anyone who lived through 2002 and 2008 knows that this is not the case. Business and capital market cycles and turn quickly and unexpectedly.

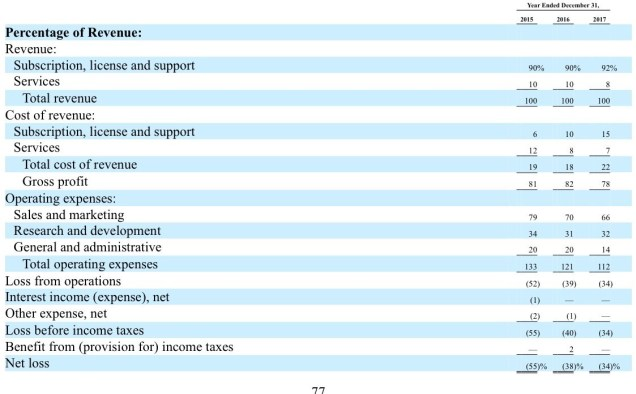

The sales and marketing battle between companies has become so intense that founders have been required to raise unprecedented amounts of money. As a result, what we see today are businesses going public with a founder who sometimes has only a three to four percent stake in the business. As a point of comparison from an earlier era, Bill Gates alone owned more than 45% of Microsoft when it went public. The sales and marketing spending required to grow a business in earlier times was not the same as it is today. As a current example of high sales and marketing spending, this below is an S-1 filing from a recent public offering. The percentage of revenue devoted to sales and marketing is remarkable by historical standards.

It can be hard to determine the effectiveness of sales and marketing spending. John Wanamaker was a very successful retailer who started one of the first department stores in the United States. His chain of department stores grew to 16 and eventually became part of Macy’s. He said once: “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.” In a modern business world that 50% is wasted figure for advertising is too low. Businesses like Costco and Amazon have shown that it increasingly makes sense to spend money on benefits for the customer instead of shouting about how great the products are.

If paid sales and marketing does not scale well, what does a business do? The alternative is to generate growth “organically” based on the nature of the product and how people interact with other people and the products. Inorganic customer acquisition will typically require additional cost of goods sold (COGS), but if the approach is done correctly, it can be the most effective way to acquire customers. Some successful startups do not advertise at all until they reach significant scale. As an example, the growth teams that Chen writes and talks about are responsible for optimizing business models like freemium. The essence of the freemium business model is to reduce customer acquisition cost (CAC) when compared to the paid alternative (e.g., based on paid advertising). Freemium is an organic customer acquisition strategy which lowers CAC sometimes at the cost of higher cost of goods sold (COGS) in order to produce a higher LTV and increased growth. Customers acquired organically are of higher quality for the service provider (e.g., they churn less) than customers acquired via paid marketing (inorganic). My blog post on freemium is here.

- *“The Paid Marketing Shark Fin happens when CAC [customer acquisition cost] goes up over time, causing unprofitability, which then drives budget cuts, slower growth, and more cuts.” “The first mistake is to start by thinking of everything as Blended CAC – dividing all your acquisition against dollars – as opposed to understanding CAC of each channel (Facebook, Google display, Google AdWords, etc.).

A business with access to modern data science tools and systems which believes its customers can be understood well enough by looking at averages is missing a huge opportunity. Customers are far more heterogeneous than most people imagine. These tools and systems can give a business the ability to differentiate on a customer-by-customer and sales-channel-by-sales-channel based on transaction logs. Professor Peter Fader of Wharton points out:

“In the old days, when we didn’t have the ability to see and measure differences, we had no choice but to create this idea of the average customer. But today, because of technology and the strategic importance of understanding customer differences, that’s no excuse. In order to survive, businesses need to understand the differences in their customers’ tastes, eccentricities, etc.” “You really do need to allow for the fact that different customers are different from each other. You have some who are valuable, and some who are not so valuable; some who want to leave immediately, and some who are going to stick around for a very, very long period of time

5. *“This is an infuriating startup experience: You ship an experiment that’s +10% in your conversion funnel. Then your revenue/installs/whatever goes up by +10% right? Wrong  Turns out usually it goes up a little bit, or maybe not at all. Why is that? Let’s call this the “Conservation of Intent.” For all your users coming in, only some of them are high-intent. …Couple important lessons: Unblock your high-intent users.

For Uber, that was things like payment methods, app quality (for Android especially!), the forgot password flow, etc. …When you focus on low-intent folks, you’ll have to get creative to build their intent quickly. Things like being able to try

out the product, having their friends into the product – these are the “activation” steps that generate intent. This is really a reflection of how working on product growth is really a combination of psychology and data-driven product. You can’t

just look at this stuff in a spreadsheet and assume that a lift in one place automatically cascades into the rest of the model.”

Turns out usually it goes up a little bit, or maybe not at all. Why is that? Let’s call this the “Conservation of Intent.” For all your users coming in, only some of them are high-intent. …Couple important lessons: Unblock your high-intent users.

For Uber, that was things like payment methods, app quality (for Android especially!), the forgot password flow, etc. …When you focus on low-intent folks, you’ll have to get creative to build their intent quickly. Things like being able to try

out the product, having their friends into the product – these are the “activation” steps that generate intent. This is really a reflection of how working on product growth is really a combination of psychology and data-driven product. You can’t

just look at this stuff in a spreadsheet and assume that a lift in one place automatically cascades into the rest of the model.”

As I noted above, the customers of a business are never homogenous. Every business will have high intent prospective customers and low intent prospective customers. They will have loyal customers and flakes. Businesses have valuable customers and customers they might want to send to a competitor since they generate a highly negative net present value. It depends.

Understanding the current intent of customers is critical. The venture capitalist Mark Suster writes:

“The three most important things to do with a sales lead [are] qualify, qualify, qualify. … The reality is that no matter how much you want to sell your products, you can’t push them on a customer who isn’t ready to buy.”

What Suster is talking about applies to the work of a human-driven sales team but also to automated processes that can be reflected in a sales funnel. A funnel can have processes that are designed to increase intent, but that is a different issue than the importance of focusing on already high intent customers.

The most useful metaphor that people have found to describe a sales or conversion process is a leaky funnel:

People who are responsible for creating organic growth at businesses have been able to discover a range of processes that improve organic growth. In an e-book written based on interviews with Chen, he frames a significant growth challenge in this way:

“We live in world where it’s easy to write code, but still hard to get the code into the hands of customers and users. Luckily, the same skills that make technology products possible – the analytical thinking that drives the engineering skills for product development – can be applied to ‘engineering’ the growth of your users as well.”

Much of this engineering is based on the application of the scientific method to business processes like funnels using modern data science tools. The amount and frequency of experimentation required to discoverer optimal interactions with a prospective or actual customers process is astonishing to people who are not doing this work. And since every business and market is dynamic and constantly changing the need for this experimentation using the scientific method never ends. A skilled growth team is able to essentially discover invisible money that is harvestable by conducting rigorous growth experiments. This high positive financial return on growth experimentation in no small part explains why there is such a strong demand for data scientists and machine learning experts.

6. *“Most people, when they talk about viral marketing, are in fact talking about viral branding. There’s another segment of viral marketing [in which] the entire focus of the PRODUCT (not marketing, but deep down into the product) is getting more people to use it….“You have features in your product that either drive growth or don’t, and you have features in your product that either really help the value proposition, or don’t. These are actually pretty independent factors and you can build product features that hit each different quadrant.

The products with the best unit economics are naturally viral. They have motions that are core to the nature of the product that are naturally about sharing something with other people. In other words, a feature like sharing naturally causes other people to learn about the product and to share it with their friends. Building a product and then trying to bolt on something that is viral later is rarely successful. This means that creating naturally viral motions should be part of the initial product development process and not something cooked up later by a marketing team.

My blog post about creating and measuring product virality is here. Chen is pointing out that viral word-of-mouth marketing (e.g., the restaurant I went to last night is great) is not a product with a naturally viral motion (e.g., Facebook). It is important to keep viral word of mouth about product quality separate from a viral process that is inherent in the nature of the product itself.

- *“Many of the biggest implosions in recent history – especially ecommerce – have been due to startups getting addicted to paid marketing while fooling themselves on Customer Acquisition Costs. As spend scales, it always gets more expensive and harder to track. …“Scale effects mostly work against you in paid marketing. The longer your campaigns run, the less effective they become – people start seeing your ads too often. The messaging becomes stale, and novelty effects are real. Market performance has a reversion to the mean. Saturation is also a thing. As you buy up your core demographic, the extra volume comes from non-core, who are less responsive.”

Every business has an upper limit on growth and it is just a question of when that limit appears and not whether it appears. The point where growth plateaus for any business is determined by the size of the addressable market. Andrew Chen has written a post in which he describes a business that has saturated its market as having “jumped the shark.” That can happen when a company spends aggressively on sales and marketing in a business that simply does not have enough total addressable market (TAM) to justify the spending and then is hammered financially when sales start to plateau. This is an example of Stein’s First Law at work: “If something cannot go on forever, it will eventually stop.” To illustrate this point, SEO was once a great way to acquire customers but over time its value has significantly atrophied. SEO is still valuable, but as much as it once was. Sales channels and marketing techniques evolve and sometimes get better and sometimes worse. This “creative destruction” of sales channels and marketing approaches process is dynamic and not always pleasant for the business.

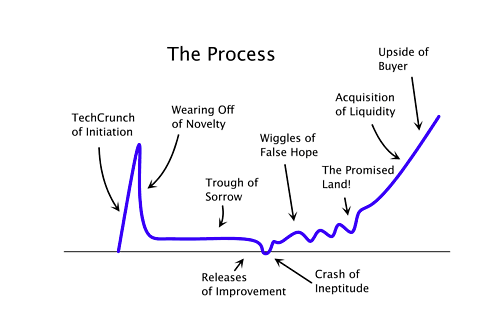

- “Getting to product/market fit is hard, and even though you feel like you’re uniquely failing, you’re actually not. Turns out every startup has to go through this, but not every startup survives it.”

The journey founders and their teams must navigate in trying to find success is not simple, steady or predictable. The middle of these journeys are messy and emotionally taxing. Stressful events inevitably happen. For example, employees and even founders can leave the business. Founders can fight. Money can disappear to a point where the business is running on fumes. The startups that survive this process that Ben Horowitz in his book The Hard Thing About Hard Things calls “the struggle” are almost always populated by missionaries who have the necessary grit to overcome the challenges.

- “Competitive dynamics are real. They’ll come in to copy not just your product, but also ad messaging and creative. It’s not hard to fast follow.”

Barriers to entry in just about any business are declining due to advances in technology and business practices. The pace of competition is increasing and in a word: relentless. People who write or say that this is not true are not engaged in a real business and inevitably are pundits of some sort. one reason why competition levels are so high that it is easier than ever to enter many businesses since many of the basic elements can be purchased on an as needed basis rather than up front. As Professor Michael Porter writes: “It’s incredibly arrogant for a company to believe that it can deliver the same sort of product that its rivals do and actually do better for very long.” Innovation that delivers sustainable competitive advantage has never been so important. One way to look at a phenomenon like venture capital funded investments is as a business experiment generating machine. Failure is an essential part of this process and progressively more failure is inevitable as more experiments are conducted. One reason why Silicon Valley is so successful is that the area has a culture that has a high tolerance for and even celebrates failure. Every business can expect scores of new experiments to be funded every year that relentlessly attack its business. Exactly zero businesses are protected from this creative destruction competitive process by the tooth fairy. Every company can be disrupted by new entrants.

- “Time to Product/Market Fit has to be less than 1-2 years or else your startup will implode. Ask anyone who’s been working on a product for more than 2 years and doesn’t have traction to show: It really, really sucks. The first 6 months can be fun because it feels like you’re painting on a blank canvas, but soon enough, there’s just fatigue and the window of opportunity shifts. Platforms change, investors get disengaged, your employees start getting excited about other companies. So if you miss your window, then you’ll run out of money or energy or both.”

A seed/early stage venture capitalist is making a bet that founder can find product/market fit. The patience of the financier is limited. Employees will also lose interest during this same time frame if the process takes to long to generate product/market fit. Wasting cash with frivolous spending during this period shortens the runway a business has to accomplish this key goal. The pressure to find product/market fit is so great that some companies pretend that they have found it and launch their growth efforts too early. This is called premature scaling and is almost always deadly. Do some businesses find product/market fit after they have started their growth phase? It can happen, but that outcome is neither a high probability event nor a wise idea. It is better to have a sound process than to rely on luck overcoming long odds.

- “Ideally the differentiation is baked deeply into the core of the product, not out on the edges. Something the end user can see and feel within the first 30 seconds of using the product.”

My blog post on what a growth team does is here. In that blog post I write about a challenge every startup faces: How can the potential customers be given an “A-ha” experience that demonstrates core product value in just seconds in ways that are almost frictionless? Chen is saying that delivering that differentiated experience quickly is a core challenge for every growth team. I could write more on this topic, but this post is already too long.

- “If you think about the idea that there’s 10-15 companies every year who are breakouts, how many people really have first-hand experience making the right decisions to start and build breakout companies?” “With so few datapoints, the prediction models we generate as a community aren’t great- they’re simplistic and are amplified with the swirl of attention-grabbing headlines and soundbites. These simplistic models result in generic startup advice. [That can be] dangerous when applied recklessly to every situation.”

Industry data undeniably shows that financial success in venture capital reflects a power law. John Doerr has put it this way: “The key insight is that actual [VC] returns are incredibly skewed. The more a VC understands this skew pattern, the better the VC.” In any style of investing it is magnitude of correctness and not frequency that matters (the Babe Ruth Effect). In venture capital, the failure rate is high enough that the math dictates that a very small number of winners will determine whether a particular fund will be financially successful. Venture capitalists are looking for significant optionality (an asymmetric upside) with a downside limited to what they invest (i.e., you can only lose 1X what you invest, but the potential upside is many multiples of what you invest).

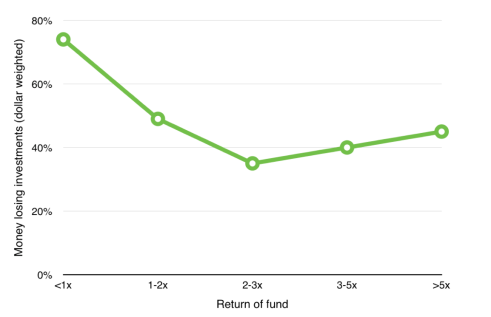

To illustrate this point, in this chart which appears in a Chris Dixon blog post the Y-axis is the percentage of investments that lose money weighted by dollars invested per investment. As you can see from the chart, failure happens often. Fortunately for skillful venture capitalists, so does a smaller number of outsize financial grand slams.

The creation of an enormous new business like Facebook is a rare enough event that people like to tell stories based on extrapolation of recent events and the particular path taken by these companies. Recency bias inevitably makes people recall and emphasize more recent events and observations than those that happened in the more distant past. Making matters worse is the fact that while stories about the path of a business in achieving that success are fun to write and read, they are not always reality-based. Michael Chrichton writes:

“Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Paper’s full of them.”

Mark Twain is often quoted as having said: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” It is wise to learn from the past, but also to expect the future to be different in important ways. Tomorrow’s important successful new businesses will break what most people thought were “rules” or best practices in important ways. That is part of what creates innovation. These breakthrough successes will not be contrarian in every aspect of what they do but the will be unique enough that so that they will have found previously undiscovered optionality.

The grand slam financial success of a new business like Google will seem obvious to some people as they recall the path of the business to success. The unfortunate reality is that financial return from investing is generated from understanding the hidden value before it is discovered, not afterward. No points are awarded in investing or business for storytelling after the fact.

End Notes:

Featured essays: andrewchen.co/list-of-ess…

Twitter: @Andrew Chen

Dixon:

Bessemer- State of the Cloud:

Fader:

knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/why…

Suster:

bothsidesofthetable.com/scaling-sal…

Bessemer: